U.S. Senate

See Full Big Line

(D) J. Hickenlooper*

(D) Julie Gonzales

(R) Janak Joshi

80%

40%

20%

Governor

See Full Big Line

(D) Michael Bennet

(D) Phil Weiser

55%

50%↑

Att. General

See Full Big Line

(D) Jena Griswold

(D) M. Dougherty

(D) Hetal Doshi

50%

40%↓

30%

Sec. of State

See Full Big Line

(D) J. Danielson

(D) A. Gonzalez

50%↑

20%↓

State Treasurer

See Full Big Line

(D) Jeff Bridges

(D) Brianna Titone

(R) Kevin Grantham

50%↑

40%↓

30%

CO-01 (Denver)

See Full Big Line

(D) Diana DeGette*

(D) Wanda James

(D) Milat Kiros

80%

20%

10%↓

CO-02 (Boulder-ish)

See Full Big Line

(D) Joe Neguse*

(R) Somebody

90%

2%

CO-03 (West & Southern CO)

See Full Big Line

(R) Jeff Hurd*

(D) Alex Kelloff

(R) H. Scheppelman

60%↓

40%↓

30%↑

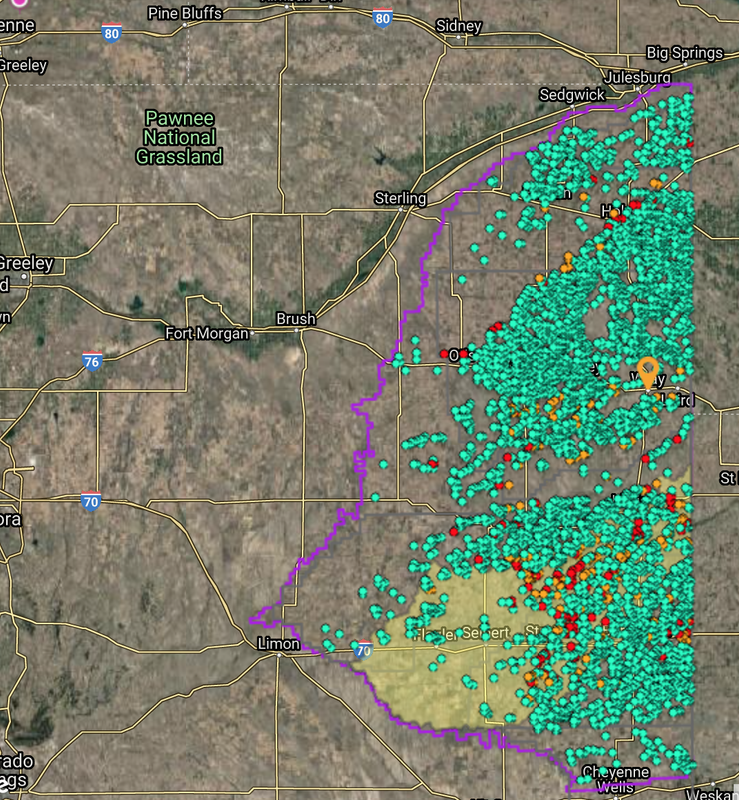

CO-04 (Northeast-ish Colorado)

See Full Big Line

(R) Lauren Boebert*

(D) E. Laubacher

(D) Trisha Calvarese

90%

30%↑

20%

CO-05 (Colorado Springs)

See Full Big Line

(R) Jeff Crank*

(D) Jessica Killin

55%↓

45%↑

CO-06 (Aurora)

See Full Big Line

(D) Jason Crow*

(R) Somebody

90%

2%

CO-07 (Jefferson County)

See Full Big Line

(D) B. Pettersen*

(R) Somebody

90%

2%

CO-08 (Northern Colo.)

See Full Big Line

(R) Gabe Evans*

(D) Shannon Bird

(D) Manny Rutinel

45%↓

30%

30%

State Senate Majority

See Full Big Line

DEMOCRATS

REPUBLICANS

80%

20%

State House Majority

See Full Big Line

DEMOCRATS

REPUBLICANS

95%

5%

May 15, 2021 04:27 PM UTC

May 15, 2021 04:27 PM UTC

Comments